After being stranded in Kabul following the Taliban takeover, journalist Sonia Sarkar managed to leave on an Indian air force plane, but with no luggage

She describes how her taxi driver negotiated to get her to the Indian embassy, and seeing hundreds of desperate Afghans near the airport, waiting to flee

New Delhi-based journalist Sonia Sarkar arrived in Kabul last week intending to report on the implications of the conflict between Afghan forces and the Taliban on the back of the US troop withdrawal. After the Taliban entered Kabul on Sunday, sparking a mass evacuation of diplomats and civilians by the United States and its allies, she got in touch with the Indian mission in Kabul, which helped her return home. Here is her first-person account of leaving Afghanistan.

As chaos broke out at the Kabul airport on Monday fuelled by Afghans fearful of living under a Taliban regime, my local contacts advised me to stay put and not leave my hotel. One of them, who had been out and about in the Taliban-controlled areas of other provinces, texted me to say: “Pull your curtains shut, they are out on the streets”.

But I wanted to return home. By then, I had learnt that commercial flights would be suspended and the seats I had secured on two flights leaving Kabul for India would not be able to take off as scheduled on Tuesday.

What made me more worried was local women contacts who asked if I had left the country. The Taliban had started looking for female Afghan journalists, they said. Would they do the same to foreign women journalists, I asked?

“But you are Indian,” came the reply, reflecting what I had heard during my short time in Kabul, that “Afghans love Indians but the Taliban hates Indians”.

New Delhi has strongly backed the Kabul government and opposed the Taliban, with no direct channels of communication between them.

As I contemplated my next move, the Indian embassy got in touch with me and a fellow female Indian journalist. They told us to reach the embassy quarters in the next two hours as they planned to leave Kabul in an Indian air force aircraft late at night. My suitcase was already packed.

I hurriedly called a reliable local taxi driver who said he would take some time to reach me. I later found out that he had to battle through a maze of traffic as he was coming from Arzan Qimat, a neighbourhood in far eastern Kabul, near the Pul-e-Charkhi prison. Hundreds of inmates had walked free soon after the Taliban took power on Sunday, while residents were rushing out to draw money and get supplies.

When I gingerly stepped out of the hotel the street outside was deserted but I could see men dressed in shalwar kameez, the traditional clothing of Afghanistan, patrolling neighbouring streets. Some had set up checkpoints and were stopping vehicles. They were carrying what looked like Russian-made Kalashnikov rifles.

After picking up my fellow journalist, we headed for Wazir Akbar Khan, the diplomatic enclave in Kabul.

A group of Taliban stopped us at the entrance to the enclave. They scrutinised our passports then told us to return the next morning.

We could not leave. It would have meant missing our chance of exiting the country. And I feared I did not have any place to go as I had checked out of the hotel, and later learned it was full of Taliban fighters. So we waited in the taxi for three hours before we approached them again.

The taxi driver was able to convince them that it was imperative for us to pass. But one of the Taliban, a man who looked to be in his 20s, said it was getting dark and as we were women, we could not walk into the compound on our own.

Finally, a member of the Indian embassy called one of the Taliban mediators to speak to the men manning the entrance, and they told us to get onto their green “police” vehicle – that they had taken from the erstwhile Afghan security forces on Sunday.

My fellow journalist and I were hesitant but worried that saying “no” would invite trouble, so we threw our luggage on the back and then climbed onto the back seat. Barely 100 metres (330 feet) from the embassy, the vehicle stopped and we were met by an armoured car belonging to the Indian mission.

Once we entered the gates of the embassy, a wave of relief swept over me.

It wasn’t clear when the plan was to leave for the airport because negotiations were under way with the Taliban to let Indian diplomats have safe passage to the airport. An embassy official told me that a day before, some people had been allowed to leave but other Indian nationals were stopped.

“We are at the mercy of their whims,” the official said.

Journalist Sonia Sarkar on a military plane leaving Afghanistan, along with 120 other Indian citizens being evacuated from the country. Photo: Sonia Sarkar

Afghan men and women sit on the road at the entrance to the airport in Kabul, desperate to leave the country. Photo: Sonia Sarkar

At about 10pm local time on Monday, we were suddenly called to assemble, and board the cars. We were ready to leave but many of us could not bring our bags, as we were told the priority was to evacuate people, not luggage. So I left a suitcase full of clothes behind.

This time, the Taliban forces escorted a convoy of 22 armoured vehicles to Kabul airport, where a military aircraft was waiting to evacuate over 120 Indian citizens after New Delhi decided to shut its mission in Afghanistan. Sources said the Taliban had promised to “take care” of the embassy’s property and vehicles, and would hand them over when the diplomats returned.

Near the airport, we saw hundreds of men walking on the streets, many carrying sophisticated weapons. As we got closer, we saw women and children too. None were carrying luggage and looked like they had left their homes in a hurry.

Each time the crowd became unruly, the Taliban fighters patrolling the street would shoot into the air. In a span of 30 minutes, I heard them open fire three times. The civilian men were kept on one side, while the women, some carrying infants wrapped up in blankets and children with schoolbags on their backs, looked petrified and stood on another side.

On Sunday night, over 640 people were evacuated in a US Air Force plane which flew to Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar. Perhaps these people were expecting to do the same.

Since its shock seizure of Afghanistan’s capital, the Taliban has furthered its sophisticated propaganda through a news conference in which it declared that it wants peace and that it will respect the rights of women within the framework of sharia, or Islamic, law. On Tuesday, more women appeared on the streets of Kabul.

A military aircraft evacuates over 120 Indian citizens from Kabul. Photo: Sonia Sarkar

A female broadcaster for Tolo News, Afghanistan’s largest private broadcaster which lost several journalists to Taliban attacks over the years, interviewed a Taliban official while several female reporters conducted interviews on the street.

But my local women friends told me that they are still fearful of stepping out of their homes.

“The Taliban claim that they will not harm women at work, but we cannot believe their words,” a postgraduate student in Kabul university wrote to me late on Monday night.

It was the early hours of Tuesday by the time our group walked past a Lebanese restaurant and a cafe to reach the airport terminal for our flight.

Some US soldiers were sleeping on the floor while another group was busy making the exit smooth. As we took the stairs to reach the waiting room, they offered us water and made us wear a white wristband. After some minutes, Indians were asked to take off the bands and directed towards the aircraft.

It was about 5am. As I fastened my seat belt, I texted my sister to say the aircraft would take off soon.

I realised, as a foreigner in Afghanistan, I had the option to leave this country. Unfortunately, millions of Afghans don’t.

Sonia Sarkar is a journalist based in India for the past 17 years. She writes on human lives, conflict, religion, politics, health and gender rights from South and Southeast Asia. Her work has appeared in a range of international publications including Al Jazeera, British Medical Journal, Ozy.com and Nikkei Asian Review. She loves to travel and considers the world as her “beat.”

My story was published in South China Morning Post, 18 August, 2021 : scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3145543/how-i-left-afghanistan-taliban-escort-airport

India’s LGBTQ community urges Supreme Court to recognise ‘fundamental’ same sex marriage rights

Posted on: March 23, 2023

- In: LGBT | Relationships

- Leave a Comment

In a sign of shifting values, members of India’s LGBTQ community are petitioning for the Supreme Court to

legally recognise same-sex marriages

India struck down a colonial-era ban on homosexuality in 2018 but the socially conservative country of 1.4

billion has to be more accepting

Sonia Sarkar

Archee Roy, 34, a queer Dalit artist in the eastern Indian city of Kolkata, has been in a committed same-sex relationship for over four years. However, she cannot list her partner officially as family in office and bank records even if they were to marry, as India does not legally recognise same-sex marriages.

“India provides a space for heterosexual couples to marry but that space and right is denied to us completely,” said Roy, who belongs to the so-called low caste Dalit community. “Queer people also deserve the right to marry, like any other citizen of India.”

This may soon change, after India’s Supreme Court on Monday referred 19 petitions to a five-judge constitution bench for consideration, with the final arguments scheduled for April 18.

In a sign of shifting values and a challenge to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government that has opposed gay marriage, members of India’s LGBTQ community are petitioning for the nation’s Supreme Court to legally recognise same-sex marriages.

The petitions come four years after the same court struck down a colonial-era ban on homosexuality. Many same-sex couples in India solemnised their marriages after the South Asia nation decriminalised homosexuality in 2018 but their marriages remain legally unrecognised.

This means that they are not entitled to rights to own and inherit property together or apply for joint bank loans. They also do not get benefits that heterosexual spouses are entitled to from their spouses’ workplace, such as pensions, bereavement leave and compassionate leave.

“The common thread among all the prayers of different petitioners before the Supreme Court is that same sex couples come within the legal framework entitling them to the benefits as well as protection that married heterosexual couples enjoy,” said Aparna Mehrotra, litigation associate at Bangalore-based non-profit Centre for Law and Policy Research, who is representing three transgender petitioners

Mumbai-based rights activist Harish Iyer appealed before the Supreme Court earlier in March to strike down provisions of this law that interfere with an individual’s constitutional rights to be treated equally, and to extend the law to marriages regardless of the gender, sexual orientation, and sexual identity of the couple. “The privilege to get married is a fundamental aspect of the right to life, freedom of speech, and privacy, as recognised under the Indian Constitution,” Iyer said.

Hyderabad-based Jojo, who prefers to use his first name, runs Queer Nilayam, a support group for LGBTQ people. The 39-year-old said marriage is significant for many same-sex couples who are in committed relationships, to avail themselves of their basic rights and benefits. India also legally recognises marriage of transgender people who hold a certificate documenting the gender

change, but the procedure for obtaining these certificates is onerous and officials often insist on medical proof of gender affirmation procedures, which can be prohibitively expensive.

Akkai Padmashali, the first transwoman whose marriage was legally recognised in India in 2018, submitted a

petition in the Supreme Court in January urging the court to define “spouse” as gender-neutral within the

Special Marriage Act. This would allow transgender people who have not yet obtained certificates or

undergone surgery to be legally wed.

As of now, transgender couples, whose marriages are registered, can be parents legally but for same-sex couples, only one partner has the legal right to adopt or be a legal parent.

In a filing to the Supreme Court this month, Modi’s administration said it opposes recognising same-sex marriages and urged the court to reject challenges to the current legal framework brought forth by LGBT couples.

The government also said in the filing that marriage is accepted “statutorily, religiously and socially” only between a biological man and a biological woman, and that the Indian family consists of these two people and the children born out of their union.

But sociologist Shiv Visvanathan argued that there is no “ideal model” of family as the concept changes according to time, ecology, demography and livelihood.

Visvanathan added that the government is including religion because it considers itself to be the “repository

of a monolithic truth and it wants to establish that certain things are not permissible”.

Mumbai-based non-binary lesbian Naaz, who prefers to use only their first name, said the Indian government remains “ill-informed” and “irrelevant” in current times when gender narratives have changed globally. Naaz said many queer people consider the larger LGBTQ+ community as “family” because they provide “safety” and “unconditional love”, unlike their biological families who have not accepted them as they are.

By opposing same-sex marriages, the Indian government is trying to promote the dowry system, marital rape and domestic violence that are “part and parcel” of the Indian family unit, said Hyderabad-based S Deepti, 39, who was in an abusive marriage with a heterosexual man for 12 years and entered into a same-sex relationship later.

“The government should try to eliminate the flaws in opposite-sex marriages before opposing same-sex marriages,” she said.

But litigation associate Mehrotra said the legal recognition of same-sex marriage would be insufficient, and that new definitions of “spouse” would be required in existing laws around succession, adoption and divorce.

Beyond laws, family set-ups, workplaces, and social spaces, which are still largely patriarchal, have to be more accepting, Roy said

Published in South China Morning Post, March 18, 2023:https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/lifestyle-culture/article/3213988/indias-lgbtq-community-urges-supreme-court-recognise-fundamental-same-sex-marriage-rights

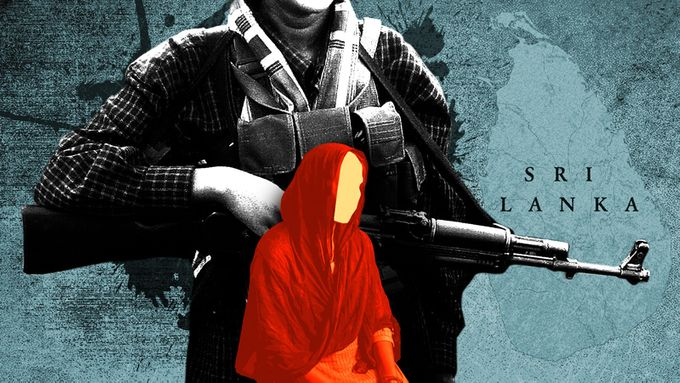

THESE WOMEN LOVED THEIR AK-47S

Posted on: January 31, 2023

| In Sri Lanka, women soldiers who once carried firearms and commanded respect now find themselves shunned. |

By Sonia Sarkar

When Malathy returned home in 2009 after serving more than a decade with the Tamil rebel group Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), she was expecting her family would embrace her with open arms. Instead, they were embarrassed by her homecoming.

“Initially, for several months, my family didn’t allow me to step out of home and talk to locals,” Malathy, a resident of Kilinochchi, a town about 37 miles from Jaffna, the capital of Sri Lanka’s Northern Province, told OZY. “They even blamed my previous association with the LTTE for the rejections that my younger sister faced in matchmaking.”

Malathy, who asked to be identified only by her first name, had served in the LTTE since she was just 16 years old. She and her family are of Tamil ethnicity, which means they are minorities in Sinhalese-majority Sri Lanka. The Sinhalese held high-ranking roles during colonial rule, and the Tamil people have faced discrimination from their government ever since the island nation gained independence from the British in 1948. The post-colonial years saw anti-Tamil pogroms that led a group of Tamil revolutionaries to found the LTTE in 1976, with the goal of creating a separate sovereign state called Tamil Eelam. In 1983, a civil war erupted between the LTTE and the Sinhalese-dominated Sri Lankan army. That war lasted 26 years.

Women like Malathy made up as much as one-third of the LTTE forces, which enlisted thousands of children as well as women into its ranks and used many of them as human shields. At least 40% of the LTTE’s suicide attacks were carried out by women combatants, with rebel leaders instructing women to hide explosives in their undergarments and then infiltrate high-security zones. (The FBI has credited the LTTE with pioneering the modern suicide belt and the use of women in suicide attacks.)

Sri Lanka has lately seen renewed upheaval following the economic collapse that led to the ouster of its president last July. Notably, amid recent street demonstrations, protesters in the capital city of Colombo openly mourned Tamil casualties from the civil war.

That civil war killed more than 100,000 people, maimed over 110,000 and left thousands of LTTE cadres — including women like Malathy — in a terrible lurch.

Attacked

Malathy and many other women of the LTTE felt powerful during the years they spent with AK-47s and T56s hanging around their shoulders.

Although Malathy served primarily in the LTTE’s communications arm, she went through rigorous training that included practice with martial arts and firearms, as well as other military exercises. She even wore the LTTE trademark cyanide capsule around her neck, to swallow in case she was captured.

That’s in stark contrast to her post-war life, in which she resides with a family that’s embarrassed of her association with the LTTE, in a village where police officers and military servicemen monitor her whereabouts and interrogate her about her past.

(Although the Sri Lankan army eliminated the Tamil guerrillas 13 years ago, some former combatants have been arrested and intimidated amid allegations of regrouping themselves for future attacks.)

“My life at home is no less than an exile, it was much better in the jungles,” said Malathy. She is one of many women who served the LTTE and are now searching for acceptance and a new role in Sri Lankan society — and even within their own families.

Human rights activist Ambika Satkunanathan has pointed out that the inclusion of women in the LTTE was “strategic,” and “driven by military needs,” and not done with the aim of addressing gender inequality. Kilinochchi-based activist Sathiyamoorthy Lalitha Kumari, who works for the rehabilitation of women war victims, said that these women were considered “brave” and “powerful” in Sri Lankan society when they carried arms, whereas they are now “looked down upon.”

Strictly defined domestic roles were, in part, what Tamil women hoped to escape nearly four decades ago when they joined the LTTE. Kumari said women were attracted to the LTTE for its promise to abolish caste discrimination and feudal customs such as the dowry system, and usher in social, political and economic equality. Like male combatants, many women believed the onus was on them to fight the repression of Tamils in Sinhalese-majority Sri Lanka, said Kumari. Also, while some women joined the LTTE to escape sexual harassment or rape by Sri Lankan soldiers, there were others forcefully recruited by the rebels.

But female combatants have been ostracized in their return to “normalcy,” even if most Tamil people once supported the rebel group, said Christine Sixta Rinehart, professor of political science at the University of South Carolina Palmetto College. Rinehart, who has studied the LTTE movement, told OZY that patriarchal societies like the one in Sri Lanka are “not yet ready” to see women outside of traditional gender norms.

“Physically strong women, who once used weaponry and challenged gender roles by taking a more masculine persona, are difficult for these societies to accept,” said Rinehart.

Although women played an active role in the Tamil nationalist struggle, there was no fundamental change in gender roles within the Tamil community, said Satkunanathan. Discriminatory practices simply reemerged when the armed conflict ceased.

Return to ‘Normalcy’

The Sri Lankan government claimed to rehabilitate 12,000 LTTE militants between 2009 and 2012, in an effort to reintegrate them into society. In the case of women, that effort was geared toward making the ex-combatants more “feminine” by training them as makeup artists, seamstresses and nursery school teachers.

Today, Malathy works at a local grocery shop. She tried but failed to borrow a sum of 500,000 Sri Lankan rupees, or about $1,360, to establish a photography studio. It would have been a rare studio run by a woman in her village, Malathy said.

She dreamt of using her photography skills, which she honed during her LTTE days, to become financially independent, and she had hoped to train local girls in photography as well.

A former combatant who asked to be referred to only as Lakshmi told OZY that she wanted to teach self-defense lessons to local girls. But locals refused to send their children to her. Lakshmi, now 41, suspects that parents worry she would teach the children something “bad” and influence them to become “immoral.”

“People don’t want girls to be self-dependent because that would mean she would defy societal norms,” Lakshmi said.

Based on interviews with 20 ex-combatants, the Routledge Handbook of Human Rights in Asia found that business loans have not provided sufficient economic stimulus to women who served the LTTE, and that they continue to have difficulty finding other work.

These women face other challenges too. Satkunanathan said there have been human rights violations in the form of sexual abuse during the so-called rehabilitation process. Rinehart said women who served in the LTTE are more likely to be viewed as “loose” by men.

“People don’t think we deserve to be part of the society,” said Malathy. “They want us to remain isolated.”

The story was published in OZY:https://www.ozy.com/pg/newsletter/the-daily-dose/455544/- January 12, 2023

An ode to Pele, and my father, who got a glimpse of ‘black pearl’ in 1977

Posted on: December 30, 2022

Pele at a press conference in Delhi, 2015. Credit: Sonia Sarkar

Sometimes, you feel that your life has come to a full circle when you do what your parents have done many years ago. For me, one such moment was when I saw the legendary footballer, Pele, in 2015, 38 years after my father saw him at the erstwhile Dum Dum Airport, when he was visiting Calcutta in 1977.

My father, who was part of the football frenzy crowd at the airport on September 22,1977, had recalled the chaos to get a glimpse of “black pearl.”

“People gathered at the airport four hours in advance to get a glimpse of Pele. There was complete madness. My best friend, Shitey, and I were on my Lambretta scooter outside the airport, waiting for Pele to come out..That’s when the police lathicharged. It was a complete pandemonium. We got a glimpse of the man and stood numb for a few minutes,” — my father, who played football for years in the ’60s and ’70s, had told me.

I have heard this little anecdote so many times from my father that I realised that even for my atheist father, Pele was no less than god.

In 1977, Pele went to Calcutta with the touring New York Cosmos team and played an exhibition match against Mohun Bagan to a packed Eden Gardens Stadium on September 24. The match ended 2-2 and since then Pele is one of the football’s biggest icons that the city prefers to identify itself with.

But unlike 1977, the airport in Kolkata in 2015 didn’t witness the madness upon his arrival. It, however, slowly caught up and many tried to get a glimpse of him when his convoy was struggling to make its way through the five-star hotel in Alipore, where he stayed for three days. During his stay in Kolkata, he inaugurated a Durga Puja pandal.

Later, he came to Delhi.

Pele was in Delhi for the final of the Subroto Cup, which was played between India U-17 and Indonesia’s Daftar Nama Kontingen at the Ambedkar Stadium.

Pele was very surprised to know that more than 32,000 children participate in the tournament every year. He insisted that the importance should be on the young players. He walked with a stick as his chief security staff Ben held him from the other side.

He was keen to visit Taj Mahal but his schedule did not permit it.

One of the officers who closely interacted with Pele during his stay in Delhi had told me that he felt “claustrophobic” to see the unruly crowd in Calcutta. “People swarmed… he found it very suffocating,” he said.

Even when I had asked the legend about his Calcutta tour during a press conference in Delhi, he just said, “the city has become big.” But he added, he was “emotional” about Calcutta because of the crazy football lovers.

Pele said that he would like to tell the youngsters to learn to be a part of a team, something which his father had told him.

But people also got a glimpse of his sense of humour in Calcutta. At a press conference, someone asked, will there be another Pele? He had said, “my parents have closed the machine.”

Pele, who preferred light eating, limited himself to meat seekh with vegetables for lunch and fish with wine for dinner. The organisers did not ask him to try anything “Indian”. “We just gave him what he wanted,” one of the IAF official said.

India’s drought-hit farmers make a fruitful pivot to ‘the only crop that can survive’: hardy dragon fruits

Posted on: December 28, 2022

Indian farmers favour dragon fruits for their profitability, resistance to pests, ability to grow in arid conditions and comparatively low water needs

The high profit margins have even attracted interest from affluent professionals – but not everyone has enjoyed the fruits of their investments

Dragon fruit is gaining popularity as the crop of choice for India’s fruit farmers, who favour it for its profitability, resistance to pests, ability to grow in arid conditions and comparatively low water needs.

Siddhu Arani planted 1,600 dragon fruit saplings in drought-hit Maroli village, Maharashtra state, nearly a decade ago. Within three years, the 50-year-old fruit farmer had not only recovered her initial 600,000-rupee (US$7,250) investment but was actually making an annual profit of 400,000 rupees.

“The annual profit is 50 per cent more as compared to my earnings from grapes and pomegranate that I cultivated before,” she told This Week In Asia. “In drought-affected areas, dragon fruit is the only crop that can survive.”

Anuradha Anandrao Pawar with some of the dragon fruits her and her 80-year-old farmer-husband Anandrao Baburao Pawar have cultivated. Photo: Handout

Several farmers, who previously cultivated traditional crops in the semi-arid and drought-hit regions of Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, have over the past six years started to grow dragon fruits instead.

This “exotic” fruit with scaly spikes and high nutrient values was grown only in home gardens thirty years ago, but by 2020, 12,000 tonnes of dragon fruits were being produced annually in India in some 4,000 hectares of land. Cultivation will further expand to 50,000 hectares of land in the next five years, according to the Indian Council of Agricultural Research – National Institute of Abiotic Stress Management.

China, Vietnam, and Indonesia currently account for about 93 per cent of global dragon fruit production, but India is muscling in on the market. This year, India exported 1,150 shipments of dragon fruits to Nepal, Maldives and Bhutan, after also shipping the fruits to the UK and Bahrain the year before.

Goraksha C Wakchaure, a senior scientist at the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, said that dragon fruits had come to the “rescue” of Indian farmers facing climate change-related disasters such as frequent droughts, floods, land degradation, extreme temperatures and pestilence.

Dragon fruits, he added, can be cultivated in degraded land and drought-prone areas, across diverse temperature ranges.

They are also resistant to pests and requires less water than other plants such as sugar cane, said 80-year-old Anandrao Baburao Pawar, one of the 700 dragon fruit farmers in Maharashtra’s Sangli district. At summer’s peak, an acre of dragon fruit crop requires about 3,000 (13,600 litres) of water each week. Sugar cane plants, by comparison, need eight times that amount.

Siddhu Arani’s farm produce. Credit: Siddhu Arani

NV Deshpande, director of the Yerala Projects Society – a non-profit organisation that helps implement innovative farming techniques in drought-affected areas – said dragon-fruit farmers were able to recoup the initial capital cost for one acre (o. 4 hectares) of cultivation – 350,000 rupees – within three years, while also making 400,000 rupees in cumulative profits. Maintenance costs about 30,000 rupees annually.

This makes dragon fruit cultivation more profitable than growing grapes, for example. Cumulative profits from one acre of grape cultivation barely reach 100,000 rupees over three years, Deshpande said, yet farmers must spend 250,000 rupees on upfront costs and the same amount on yearly maintenance.

Lata Aigale, a farmer in Ajur village of Karnataka’s Belgaum district, said she hoped that the authorities would make it easier for dragon-fruit farmers – who often struggle with start-up costs – to access government subsidies.

Lata Aigale (front) pictured with her dragon-fruit plants in Belgaum district, India’s Karnataka state. Photo: Handout

Farmer Pawar’s 1,320 dragon fruit plants, which occupy one acre of land, yielded 200kg of fruit in 2017, 1.7 tonnes in 2018, and 6.6 tonnes in 2019.

He then planted 3,280 additional saplings over another acre of land and together those two acres yielded 9.2 tonnes of fruit this year, earning him 820,000 rupees (US$9,900) in profit.

In Madhya Pradesh’s Chiklod village where temperatures can hit 45 degrees Celsius in summer, horticulturist Amitesh Argal, 30, started dragon fruit cultivation last year in rocky, sandy soil that repelled water. Still, he expects to recover his capital investment of 700,000 rupees within the next two years.

Deshpande said dragon-fruit farmers in Maharashtra make profits every year, unlike grape growers, who often owe debts of at least 300,000 rupees at the end of the growing season.

Many debt-ridden Indian farmers, hit by higher production and transport costs – on top of intense drought conditions – have taken their own lives over the past two decades. Last year, 5,563 agricultural labourers died by suicide, with the highest toll being in Maharashtra, with 1,424 deaths.

The profitability of dragon-fruit cultivation is also attracting investments from affluent professionals.

Investment banker Parth Mirani invested 6 million rupees (US$72,400) in 2018 for nine-acres (3.6 hectares) of dragon fruit cultivation in Central India’s Chhattisgarh state – where the climate is dry throughout the year – which made him an annual profit of 2.5 million rupees from the third year on.

But not all investments have been so successful. Kalpesh Hariya, director of Auroch Agro Products, and his two partners invested some 10 million rupees in six hectares of land in Gujarat’s semi-arid Kutch district in 2014.

The results were poor, at first. Hariya said yields only started to improve in 2016 after they had lowered the soil’s pH level, making it less alkaline, and replanted more than 18,000 saplings. A year and a half later, they harvested some 14 tonnes of fruit.

For Mirani, the investment banker, dragon fruit will soon stop being regarded as “exotic” as large-scale production reduces cost.

Retail prices for dragon fruit have been on the decline in India recently. A year ago, one dragon fruit would set you back almost US$2 in most big Indian cities, whereas now they can be picked up for about 60-80 rupees (72 US cents to 97 US cents) each.

[Published in South China Morning Post — https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/article/3204362/indias-drought-hit-farmers-make-fruitful-pivot-only-crop-can-survive-hardy-dragon-fruits

Date: 25 December, 2022]

Finding painful common ground

Posted on: December 27, 2022

Many Sinhalese Sri Lankans took to the streets to protest against the economic pain they are enduring. Now they are realizing how the minority Tamils suffered, particularly during the decades-long civil war.

Photographs of people disappeared in 26-year-long civil war. Credit: Sonia Sarkar

Mass protests, or aragalaya, are no longer a daily affair in Sri Lanka. The demonstrations that helped oust a government a few months back are far from being over, though. Current President Ranil Wickremesinghe has even threatened to arrest those planning yet another aragalaya, but Sri Lankans reeling from the effects of a severe economic downturn may not be in the mood to heed his words.

Yet while the aragalaya reflect the breakdown of the relationship between Sri Lanka’s people and their leaders, the protests seemed to have opened an opportunity for dialogue between the majority Sinhalese and the minority Tamils. With the participation of people across class, caste, religion, and region, the aragalaya even raised hopes for reconciliation between the two communities that have generally had trouble getting along.

“A large section of Sinhala people have been indifferent toward the plight of Tamils as the latter were projected as an enemy of the country by successive central governments,” says Ceylon Teachers’ Union General Secretary Joseph Stalin, who has been a regular at aragalaya that began early this year.

But now, he says, “Sinhalas have realized that the suffering of Tamils has been ignored for too long.”

Sinhalas and Tamils sit at a protest against government over disappeared people in 26-year-long civil war. Location: Kilinochchi.

Credit: Sonia Sarkar

About 75% of Sri Lanka’s 23 million people are Sinhalese, most of whom are Buddhist. The Tamils meanwhile make up about 15% of the country’s population. Most Tamils are Hindus; a significant number are Muslim while there are also Christian Tamils.

Between 1983 and 2009, parts of Sri Lanka became stages for savage warfare between the country’s military and the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). While the war raged, over 100,000 people — mostly Tamils — disappeared in Sri Lanka. For decades now, Tamils have been looking for their missing fathers, husbands, sons, and daughters. But the majority Sinhalese population barely paid any attention to their plight, with many saying simply that it was not their fight.

In fact, for the first time, Kulandaivel Sumitra Devi, a Tamil who has been looking for her husband who went missing in 2008, says that she is hopeful that the government may finally begin listening to people like her. She says that this is because a section of the Sinhalese population is finally standing by the side of Tamils.

“Since the Sinhalese activists have expressed their empathy toward us, we are hopeful that our pleas will be answered now,” says Sumitra Devi, 42, a resident of Ampara in Eastern Province. “Unfortunately, the Sinhalese people took more than three decades to stand by us, to hold our hands.”

Army checkpoint at Kilinochchi. Credit: Sonia Sarkar

Been there, done that

On Aug. 12, Sumitra Devi, along with hundreds of other victims of the civil war from northern and eastern provinces — the traditional Tamil homeland — gathered at Kilinochchi, about 100 km from the Northern Province’s capital Jaffna, demanding justice. They were joined by over 35 Sinhala students, activists, and civil society members, who had traveled about 350 km from the country’s capital Colombo to express solidarity with them.

Earlier, on May 18, hundreds of citizens including Sinhalese Buddhists gathered at Colombo’s Galle Face Green, an open public space overlooking the Indian Ocean. The site had been the center point of aragalaya between April and July this year. The May gathering, however, was to mourn the 2009 killings of Tamil civilians in the last battle the army had fought with LTTE guerrillas at Mullivaikkal in Northern Province. For more than a decade, Colombo had celebrated the occasion as “Victory Day,” to hail the Sri Lankan army’s win in the war.

Some Tamils believe that the current nationwide economic crisis that led to severe power cuts and rising food and fuel prices has been an opportunity for people living in the west and south of the country to finally understand what Tamils had gone through during the civil war.

Ampara resident Devasahayam Ranjana, 69, says that people in the north faced power outages and economic embargoes on many consumer goods including diesel fuel, petrol, fertilizer, pesticides, and medical products during the war. She says that they also faced restrictions on fishing, imposed by the Sri Lankan government in the 1990s.

“Economic crisis is not new to us, we have seen it all,” says Ranjana, whose husband and eldest son have been missing since 2009.

Similarly, enforced disappearances, arbitrary arrests, and heavy deployment of military personnel in civilian areas — now routine in Colombo in the south ever since Wickremesinghe was elected president in July — have been fairly common in the north and east.

Sushila Devi, a resident of Batticaloa in the east, recounts how her 18-year-old son was dragged out of a bus by the Sri Lankan army personnel in 2007 while they were traveling from Trincomalee to their hometown. She says that she ran pleading for help behind the army vehicle for about 100 meters while her son, who was in the vehicle, held tightly onto the gold chain around her neck. But a soldier kicked her hard on the stomach, forcing her son to let go of her necklace. The vehicle sped away, and she was left lying on the street, devastated and in pain.

“The army never gave me my son back,” says Sushila Devi, who has even approached the International Committee of the Red Cross, seeking justice. “I have the right to know if he is alive or dead.”

The army gave no answers to Sumitra Devi either — even after she found her husband’s identity card with one of the army personnel deployed at the checkpoint near their family’s farm, just days after he went missing. She remarks, “The army never realizes that they are accountable to us.”

Detained, disappeared, dead

In 2015, former Sri Lankan President Maithripala Sirisena proposed to establish a truth and reconciliation commission. But the United Nations at the time said that the country was “not yet ready or equipped” to conduct a “credible investigation” into suspected violations.

Human rights defender Ambika Satkunanathan says that up to now, the Sri Lankan government does not have complete data on the number of people who disappeared or were killed during the war.

Satkunanathan notes that some people were issued death certificates for their family members who were victims of enforced disappearances, and were also given paltry compensation by the government. Many were forced by the government to accept these death certificates, she says, adding, “Some accepted compensation because of their dire economic circumstances.”

Satkunanathan says that information on those who were killed or disappeared can be considered complete “only if there is no sense of fear among Tamils.”

Tamils, however, continue to live in fear. According to Amnesty International, the families of the disappeared allege harassment and intimidation by law enforcement officers through unannounced visits, intimidating phone calls, and surveillance. Additionally, says the international rights watchdog, the state security apparatus of late has begun approaching the judiciary to pre-emptively restrict the victims’ freedom to protest.

Sri Lankan police also still randomly book Tamils under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) for their alleged former association with the LTTE. Just last April 25, 10 Tamils who were arrested for holding a beach memorial for the civil-war Tamil dead were finally released after seven months in detention. Human Rights Watch also points to a 2020 report by the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka that said 84% of those arrested under PTA were tortured and that some have been held for as long as 10 years without trial.

“(A) Tamil Hindu priest, arrested in February 2000 for suspected involvement in an LTTE attack, was held pre-trial under the PTA until 2015 when he was convicted and sentenced to 300 years in prison,” the Human Rights Watch said in a 2022 report. The conviction, it continued, was based on a confession that the priest claimed was “obtained through repeated torture and recorded in a language he could not understand.”

Satkunanthan says that after the end of the war in 2009, many Tamils who were not LTTE combatants were detained at military-run rehabilitation centers, in contravention of international humanitarian law. Now the same oppressive system is being extended to target those who participate in aragalaya.

Shared oppression

Satkunanathan has filed a motion at the Supreme Court against a proposed Bureau of Rehabilitation Bill that will allow the detention of possibly any citizen, bypassing the judicial system, in rehabilitation centers. She describes the bill as inconsistent with the fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution of Sri Lanka that guarantee freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention, torture and ill-treatment, and discrimination.

For his part, Mahendran Thiruvarangan, a senior lecturer in English at the University of Jaffna, agrees with the observation that Sri Lankans living in the south are now becoming aware of the atrocities against the Tamils.

Yet, he cautions that the relationship between the Tamils in the north and east, and the Sinhalas in the south, may remain precarious. Thiruvarangan says that a protest rally was held by academics, trade unionists, and civil society groups in the north to show solidarity with those holding aragalaya. But an active Tamil nationalist lobby, which demands self-determination, discouraged the sympathy protests.

According to the academic, while the nationalist Tamils acknowledged that May 18 was observed by aragalaya protesters in Colombo, the nationalists had pointed out that there was no call for political justice for the genocide of Tamils or reconciliation.

One of the main bones of contention among Tamils in the northeast is that the Sri Lankan government has been taking over religious sites of Tamil Hindus and putting up Buddhist stupas and temples in the region. Recently, there were attempts to annex two Sinhala-majority villages in the Anuradhapura district in the North-Central province to the Tamil-majority Vavuniya district in the Northern Province.

Thiruvarangan also says that lands belonging to many Tamils displaced in the war have been acquired by the military over the years. He adds that the Sri Lankan government has also tried to give a Sinhala-Buddhist character to the territories in the north under the pretext of archaeological research.

For Sumitra Devi, these attempts to “take over” Tamil-dominated areas pose a big threat to their existence. She says, “Sinhalas must oppose these attempts if they really believe that it’s time to stand by us.” ●

Published in Asia Democracy Chornicles on December 13, 2022

Link; https://adnchronicles.org/2022/12/13/finding-painful-common-ground/

Singapore is a politically passive place where an openly gay reverend is making waves.

Posted on: December 14, 2022

– by Sonia Sarkar in Singapore

Miak Siew at FCC

In June, when Singapore refused to renew the work pass of Bangladeshi migrant worker Zakir Hossain following his social media post about the living conditions endured by fellow workers, Reverend Miak Siew of the Free Community Church (FCC) took to Facebook to make a radical proposition. He suggested that, rather than punishing those with differing views, Singapore might “listen to criticism and grow.”

That was something of an unwelcome suggestion in politically docile Singapore, an island nation of 5.64 million people. A report last year from Civicus, a global alliance of civil-society organizations, demoted the country’s human rights ranking from “obstructed” to “repressed.” According to Human Rights Watch, the Singaporean government invoked a controversial statute known as the “fake news” law more than 50 times in just the first half of 2020, primarily to sanction content that was critical of the government or its policies. Authorities have also repeatedly targeted independent media outlets.

Singapore’s Ministry of Manpower said it did not renew migrant worker Hossain’s work pass because he made “misleading, false or deliberately provocative” public posts.

The plight of migrant workers is just one of many politically charged topics on which Miak Siew has been outspoken. He has made himself heard on Facebook, within his congregation, and at Hong Lim Park — the only designated place for public protest in Singapore — to decry the mounting restrictions on free speech, including the arrest of a blogger charged with criticizing the nation’s late founder, and to condemn the state’s use of the death penalty on predominantly ethnic minorities.

“If the church doesn’t speak for the voiceless, who else will?” said Siew.

‘First Realize Everyone’s Equal’

The FCC is housed in an inconspicuous industrial building in west-central Singapore, and holds services in a conference room outfitted with several large LED screens and projectors. In operation since 2003, FCC was founded by gay and lesbian Singaporean Christians after they experienced discrimination at other churches.

Siew, who studied Divinity at the Pacific School of Religion in California, has been part of the FCC since its inception. As reverend, he considers himself responsible for speaking publicly about what he views as unjust and repressive actions by the state. In April, when the government hanged an intellectually disabled man, Nagaenthran Dharmalingam, for trafficking 1.5 ounces of heroin, Siew delivered a speech at Hong Lim Park in which he asked, “What kind of society will we become when we are more compassionate, more merciful, more human?”

For those who attend services at the FCC, the word “free” in the church’s name has a second meaning: It is an acronym for First Realize Everyone’s Equal. And for many congregants, that is precisely the church’s appeal.

SL is a 44-year-old public servant and FCC congregant who asked to be identified by only her initials, as she isn’t “confident” that the government will be lenient with employees who publicly acknowledge their homosexuality. She said that Siew’s church had helped her in profound ways. The FCC, she said, “allows us to heal the wounds that we received from rejections by others.” She also noted that Siew’s strength is his commitment to “fight for the rights of the last, the lost and the least.”

But many in Singapore disagree. Critics, who have attacked both the reverend and the broader congregation, have said the FCC is not a true church, as it promotes an agenda beyond Jesus Christ.

Siew, by contrast, hopes that the FCC is in some way an answer to what he sees as a declining sense of purpose at some religious institutions.

“The churches, in many places, have lost their relevance when it stopped speaking up and it became a place of privilege and power,” he told OZY. Noting that too often, churches view baptism as their “key performance indicator,” he said this fosters a view in which baptism is the finish line. Instead, he sees baptism as the beginning of a journey, and hopes that congregants become agents of change and a blessing to others.

Joseph Lim, a ministry staff member at a nearby Methodist congregation, has called the FCC a “cult.” Lim did not respond to OZY’s request for additional comment.

Meanwhile, a spate of executions in Singapore has drawn international scrutiny as well as rare local protests. Siew has noted that a majority of those who have been executed were poor and dark-skinned.

Responsible and Balanced

When people walk into church, said Siew, they are carrying their whole life with them: their struggles for work, survival and acceptance. He said the aim of the FCC is to make people feel safe. As that happens, congregants are able to become more involved in larger causes and what he described as “helping to shape the world into a more loving and justice-oriented society.”

This year, at a public event, when he said that the predominant cause of suicide and self-harm among LGBTQ people is the discrimination they face, a psychiatrist called this claim “unnecessary and immensely unhelpful,” adding that it was tantamount to casting blame.

Siew’s outspoken ways have not gone unnoticed by the government. After Singapore announced the repeal of Section 377A (a law that banned gay sex), effectively making it legal to be homosexual, Siew wrote on Facebook that the announcement had made it easier for “us” to speak about LGBTQ topics “live on air.”

Intervening immediately, Singapore’s Ministry of Communications and Information said it was of the “utmost importance” that mainstream media continue to be “responsible and balanced” in handling LGBTQ topics.

Soon after that statement, Siew’s interview on a state radio station was cancelled. Siew called this a part of the “systemic erasure and silencing of our voices” so that “people don’t hear the stories” that will help them understand.

COMMUNITY CENTER

What kinds of issues are appropriate or inappropriate for a reverend to speak about?

Pregnant women caught in Pakistan’s floods left struggling for maternal healthcare

Posted on: November 19, 2022

Some 650,000 pregnant women in flood-hit provinces are affected by maternal malnutrition, with about

2,000 mothers a day giving birth in unsafe conditions

Unregulated use of medicines, untrained birth attendants, lack of access to health facilities and hospitals

among problems post-floods

By Sonia Sarkar

November 13, 2022

Pakistani health worker Mai Janat Buriro, 37, spends three hours every day handing out medicines to pregnant women with iron deficiency or malnutrition in the flood-affected province of Sindh.

Of the 11 mothers who gave birth last month in her neighbourhood in the Allah Rakha colony, three who suffered from maternal malnutrition lost their infants.

“Most pregnant women have nothing to eat,” Buriro told This Week In Asia. “They don’t have access to milk either because animals they reared had died in the floods.”

Over the past several months, devastating floods have killed more than 1,500 people and displaced 7.6 million people.

Health experts have said that maternal healthcare in the country – long plagued by the rampant use of unregulated medicines, heavy dependence on untrained childbirth attendants and poor antenatal and postnatal care in the backward areas of these provinces – has worsened after the floods.

Unregulated use of medicines

Neha Mankani, founder of Karachi-based non-profit Mama Baby Fund which provides essential medical services to mothers and babies, last month claimed on Twitter that untrained birth attendants in Pakistan used the veterinary drug oxytocin to augment labour during childbirth.

Mankani told This Week in Asia that this had “happened in many places for many years” because of “lack of regulation” of both drugs and untrained childbirth attendants.

This lack of strict regulation has led to “irrational and unregulated” use of medicines, and “sometimes, veterinary medicines are used in humans, and vice versa”, according Zafar Mirza, a former special assistant to the prime minister on health.

Lahore General Hospital’s medical officer Alia Haider said pregnant women in remote areas of Balochistan were largely dependent on untrained birth attendants, who could use veterinary oxytocin without any due supervision.

The non-profit Human Development Foundation said many pregnant women in Sindh province turned to untrained childbirth attendants because local facilities were non-operational and government hospitals were either too far away or inaccessible without prior connections with doctors. Photo: Mazhar Abbasi

According to a 2016 study, oxytocin, which is manufactured for humans, is given in an unregulated manner by untrained birth attendants. The study said of 6,379 women respondents, 607 (9.5 per cent) received labour-inducing medication before reaching hospital, and of the 607 women, 528 (87 per cent) received unregulated medication. Of 528 women, 94.5 per cent received oxytocin injections.

Sexual and reproductive health specialist Syed Rizwan Ali said untrained birth attendants, who have been masquerading as health workers and midwives in flood-hit areas, barely checked the expiry dates of oxytocin or syntocinon injections before administering them.

Ali visited flood-hit Balochistan and Sindh in October and found that no drug inspectors were on hand to check for medical malpractice.

Bushra Arain, chairperson of All Pakistan Lady Health Workers Association, said Sindh’s local feudal leaders – who have a political stronghold – also helped some untrained birth attendants to operate. Arain said that despite making police complaints, no action has been taken against the untrained birth attendants.

Mazhar Mehmood Abbasi of the non-profit Human Development Foundation, which advocates social change in Pakistan, said many pregnant women in Sindh’s Rind Wahi turned to untrained childbirth attendants because local facilities for institutional deliveries were non-operational while government hospitals were either too far away or inaccessible without prior connections with doctors.

Pregnant women in Balochistan’s Dera Allah Yar travelled for two hours to Larkana in Sindh on flood-ravaged roads to give birth at a tertiary hospital, Haider said, adding that some “suffered excessive bleeding because of the stressful journey”.

United Nations Population Fund data showed that as of September 2022, 1,946 health facilities largely in the Sindh and Balochistan provinces had been partially or fully damaged. The lack of services meant that “community midwives”, who are trained in assisting childbirth, stepped in to fill the gaps, said Zeba Sathar, Pakistan director of US-based non-profit Population Council.

1

The trend of underage marriages in Pakistan adds to the woes affecting flood-hit areas. According to UNICEF, 21 per cent of Pakistani girls marry before the age of 18, and three per cent before they turn 15.

Sexual and reproductive health specialist Syed Rizwan Ali said untrained birth attendants, who have been masquerading as health workers and midwives in flood-hit areas, barely checked the expiry dates of oxytocin or syntocinon injections before administering them.

Ali visited flood-hit Balochistan and Sindh in October and found that no drug inspectors were on hand to check for medical malpractice.

Bushra Arain, chairperson of All Pakistan Lady Health Workers Association, said Sindh’s local feudal leaders – who have a political stronghold – also helped some untrained birth attendants to operate. Arain said that despite making police complaints, no action has been taken against the untrained birth attendants.

Maternal Mortality

Before the floods in 2019, Pakistan’s maternal mortality ratio stood at 186 per 100,000 live births with rates of 224 and 298 in flood-hit Sindh and Balochistan, respectively.

According to Mirza, an adviser to the World Health Organization on universal health coverage, oxytocin is given to pregnant women to prevent post-partum haemorrhage during childbirth and requires specific conditions – between 2 and 8 degrees Celsius – for storage.

The drug becomes “ineffective” if the storage conditions are not maintained during the supply chain, which is a common problem in Pakistan, thereby causing women to continue bleeding despite being administered with it.

In 2019, more than 41 per cent of maternal deaths occurred due to obstetric haemorrhage.

The trend of underage marriages in Pakistan adds to the woes affecting flood-hit areas. According to Unicef, 21 per cent of Pakistani girls marry before the age of 18, and three per cent before they turn 15.

Mazhar Abbasi inspecting health conditions of women and children in flood affected Sindh. Photo: Mazhar Abbasi

Saima Bashir, senior research demographer at Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, said young women such as underage mothers and minor girls in flood-hit rural areas became pregnant soon after marriage and often did not have access to contraceptives. Nationally, only 34 per cent of married women aged 15-49 use contraceptives.

A 2017 study showed that of an estimated 10.1 million pregnancies, 37 per cent are unintended while 2.5 million children are acutely malnourished. In Pakistan, 2.5 million children are currently acutely malnourished.

Bashir feared that underage marriages, unintended pregnancies, maternal mortality rate and number of malnourished children would rise in flood-affected areas.

Mirza urged local authorities in flood-hit areas to routinely identify and register pregnant women to monitor them at every stage of pregnancy. Authorities should also facilitate eight regular antenatal visits by healthcare workers to ensure pregnant women get their ultrasounds done, and receive tetanus toxoid injections and a steady supply of iron and folic acid tablets.

“Planning their childbirth under trained hands is essential besides postnatal care of the mother and child,” Mirza said.

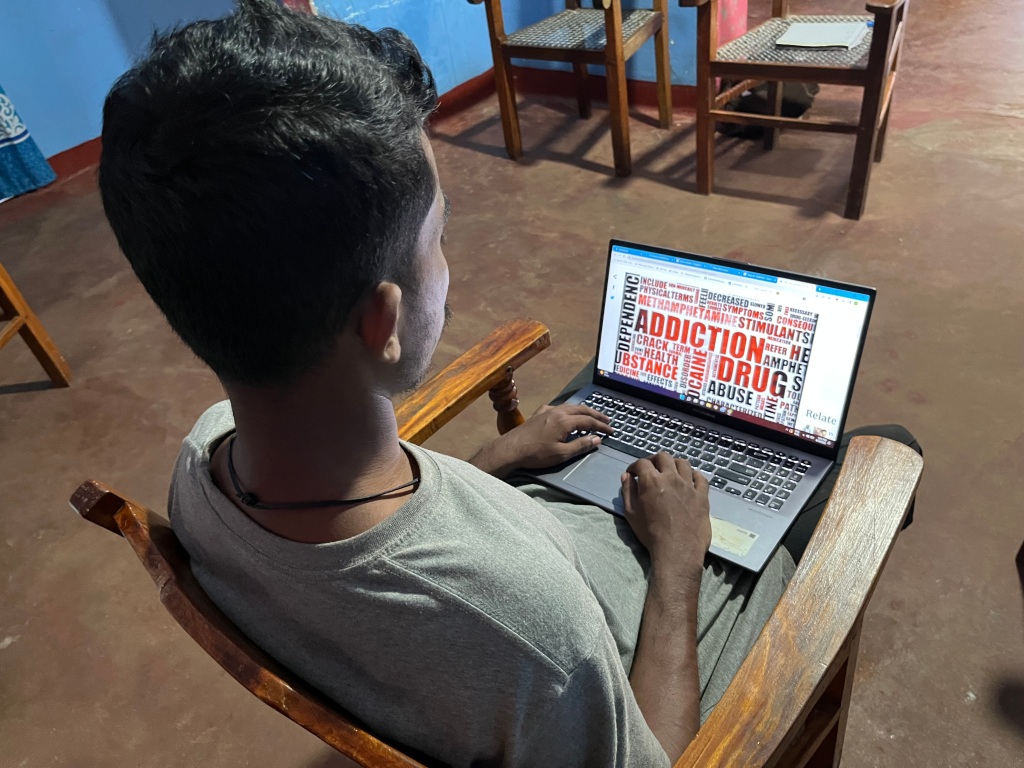

— Sonia Sarkar in Jaffna, Sri Lanka

‘I Have No Option but to give in’

Thiyash Muralitharan* was once a promising athlete in Jaffna, capital of Sri Lanka’s Tamil-dominated Northern Province. Today, the 25-year-old is among a fast-growing band of young people who are embroiled in a dangerous new crisis.

Eight years ago, Muralitharan had won several intercollegiate long jump medals, and his sports career appeared poised for a leap to the national stage. Then a friend at the local college offered the young athlete a marijuana joint — ostensibly, to help boost his stamina. Before he knew it, Muralitharan was skipping visits to the sports grounds and instead rushing to a nearby fishermen’s village to buy cannabis. He eventually started using heroin too, and now he cannot spend a day without snorting it.

“I feel normal only when I sniff heroin,” he told OZY. “I become violent when I don’t.”

His mother, Murugan Sudarshini, who sells local delicacies at a streetside stall, has had to bear the brunt of his anger.

Murugan Sudarshini at her home

“Earlier, I used to keep cash away from him so that he wouldn’t be able to buy drugs, but he physically assaulted me a few times when I refused to pay,” said Sudarshini, who now often ends up giving Muralitharan 1,500 Sri Lankan rupees (about $4) to buy a gram of heroin. “I have no option but to give in.”

Muralitharan’s addiction reflects a deeper challenge. The Northern Province, which witnessed a 26-year civil war — between the Sri Lankan army and the Tamil rebel group Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam — that killed over 100,000 people, is struggling with drug abuse. As per the latest government data, in 2019, the province recorded 12,139 cannabis users and 728 heroin users, as compared to 7,608 cannabis users and 487 heroin users in 2018.

These regional numbers are just a fraction of Sri Lanka’s national numbers, which show that an estimated 301,898 people smoke cannabis while 92,540 use heroin. Overall, about 2.5% of the national population above the age of 14 consumes narcotics either regularly or occasionally. But what’s worrying about the Northern Province is that it traditionally had lower drug use rates than other parts of the country, yet witnessed a dramatic 59% year-on-year increase in cannabis users and a 49% rise in heroin users between 2018 and 2019. And while there’s no data from the past two years yet, signs on the ground point to a deepening crisis.

Karainagar beach in Jaffna, Sri Lanka

Mid-Sea High

Apart from cannabis and heroin, methamphetamine lands in Sri Lanka’s north via the Palk Strait, the narrow strip of water separating the country from India, according to a police official who spoke on the condition of anonymity. Coastal areas, including Jaffna, Mannar and Vavuniya, are major drug trafficking hubs in the north.

Kandasami Rajachandran, president of the Ambal Fishermen’s Cooperative in Jaffna’s Karainagar, told OZY that Indian fishermen and traffickers who arrive in boats and trawlers bring these drugs halfway across the Palk Strait, where they pass them on to Sri Lankan fishermen and drug traffickers in the middle of the sea.

Rajachandran said that when the Sri Lankan navy chases local traffickers, they dump packets stuffed with the drugs into the sea. The traffickers “trace them later with the help of GPS trackers attached to the drug packets,” he added.

Sri Lankan police spokesperson Nihal Thalduwa confirmed to OZY that traffickers get the drugs through a mid-sea transfer. But he clarified that not all the traffickers are fishermen.

According to the Handbook of Drug Abuse Information 2021 released by the Sri Lankan Ministry of Defense, 97,416 persons were arrested for drug-related offenses in 2020. Of these, 11,690 are from the Northern Province. That’s 12% of total arrests even though the province accounts only for 5% of the national population.

Thalduwa said that several factors, such as shallow waters, long coastal stretches and numerous fishing boats densely parked close to the sea, make these transactions across the Palk Strait hard to stop. “Traffickers have the opportunity to park their boats in the beaches in several sparsely populated areas of the north without anyone noticing them,” he said.

Jaffna

After arriving on shore, the drugs reach schools and colleges, targeting young men. Media reports suggest that ice cream vendors often sell mava, an areca nut-based drug in the form of chewing gum, to school children. Thalduwa said that police raids have found some fast-food joints and stationery shops adjacent to schools also selling mava.

M Jeyarasa, a mental health officer at the Kilinochchi district hospital, which is about 70 kilometers (43 miles) away from Jaffna, told OZY that, while alcoholism among youth was once the biggest concern of many families, more and more parents have started complaining about drug abuse among their children. “Often, school principals and teachers seek help for their students,” Jeyarasa said. Last year, a school teacher in Jaffna was assaulted by a group of students when he criticized their alleged drug abuse.

Over 300 people have been identified as drug addicts over the past three years in the state-run drug de-addiction clinic at Kilinochchi, Jeyarasa added.

Rev. Vincent Patrick, the director of a Jaffna-based de-addiction and rehabilitation center run by a Catholic nonprofit, Change Charity Trust, told OZY that at least 15 young men in the age group of 16-27 years are undergoing treatment there at any given point. “Many are from educated families,” Patrick, also an anthropologist, said. “They start taking drugs because it’s a fad.”

Sajith, a 24-year-old computer engineer who spent over two months at Patrick’s de-addiction center in Jaffna, told OZY that he first took to marijuana because he felt it made him “creative.” In March, he started taking methamphetamine as an alternative to Ritalin — an imported medicine he used previously to treat his attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder — which became unobtainable during Sri Lanka’s economic crisis. “Meth helped me stay focused but then I realized that I was becoming violent if I didn’t take it. That’s when I sought help,” Sajith told OZY.

Sajith at the de-addiction centre in Jaffna

Broken Families

Jenushen’s neighbourhood in Navatkuli in Jaffna

Kevin Jenushen*, a 20-year-old daily wage earner who regularly uses both cannabis and heroin, remained unsupervised in his early teens because his mother, a single parent of three children and nursing assistant at a local government hospital, was busy at work. Jenushen got addicted to heroin three years ago when he was working as a fisherman — he wanted to earn to support his family — while attending college. He eventually dropped out. “Some of my college friends also got addicted to drugs while they went to the sea for fishing,” Jenushen told OZY.

Jenushen’s story is sadly common. Sypherion Thileepan, director of Shanthiham, a nonprofit that provides counseling and skills training to war-affected families, told OZY that in many families in the north, mothers are the primary breadwinners because men either disappeared or were killed during the war. That leaves children with less parental supervision, and more vulnerability.

Ambiga Sritharan, director of the Jaffna-based nonprofit Law and Human Rights Centre, which provides pro bono legal assistance to families of war victims, said that post-war trauma also left many families “dysfunctional,” pushing adolescents toward addictive substances.

But Thalduwa claimed that the police’s awareness programs in schools and colleges, aimed at preventing youth drug abuse, have helped.

Meanwhile, Sudarshini has convinced her son Muralitharan to visit Patrick’s de-addiction center. She has also convinced him to go to a nearby sports field every evening.

“I cannot do long jumps anymore, but I love to play cricket,” Muralitharan said. “My body, however, has lost the strength that a sportsperson needs.”

*Some names have been changed at the request of people who spoke with OZY but wanted anonymity. Link: https://www.ozy.com/pg/newsletter/the-daily-dose

Published on 27 October 2022.

Playing for lives: Indian state bans online gaming over addiction fears but industry cries foul

Posted on: October 27, 2022

Tamil Nadu’s ban on online games like rummy, poker will only benefit fly-by-night and illegal market operators who encourage illicit activities, says gaming federation chief

Creating awareness about game addiction, taking preventive measures would be more effective than imposing a ban, analysts say

The Indian Supreme Court has held that rummy is preponderantly a game of skill and not of chance. Photo: Shutterstock

Last year, a 45-year-old homemaker in the south Indian city of Chennai played rummy online for the first time. Placing a small bet, she was pleasantly surprised to win 500 Indian rupees (US$6) from just a 20-minute mobile game.

Feeling encouraged, she started a new game, and from then on, she began playing for six hours every day, placing higher stakes – 500 Indian rupees – for bigger returns. When she exhausted her money, she borrowed from different loan apps and her relatives. By September, she had lost over 1.8 million Indian rupees (US$21,760).

“When her relatives asked her to repay the loans they gave her, she consumed poison in an attempt to kill herself in sheer helplessness,” Chennai-based psychiatrist Lakshmi Vijaykumar, who prescribed antidepressants for the game addict, told This Week In Asia.

Elsewhere in south India, seven Tamil Nadu residents reportedly died by suicide this year following huge financial losses linked allegedly to online gaming. The deaths prompted the state earlier in October to ban online games of chance, such as poker and rummy, as well as online gambling. Those who flout the rules face jail, fines of 5,000 rupees (US$60) or both.

The gaming industry plans to challenge the ban, claiming many gamers use virtual private networks to access the games, making it difficult for the crackdown to be effective.

“The ban would only benefit fly-by-night and illegitimate market operators who encourage illicit gaming activities,” said Sameer Barde, CEO of Mumbai-based E-Gaming Federation, a non-profit that provides operating standards to its eight operator-members to self-regulate the Indian e-gaming sector and safeguard players’ interests.

Barde said an estimated 80 million Indians play rummy online, and that the Indian Supreme Court has held that rummy is preponderantly a game of skill and not of chance. Barde said he would challenge the ban because rummy is protected under Article 19(1)(g) of the Indian Constitution.

A person who plays a game of chance wins or loses by sheer luck, while one must use knowledge and expertise to win a game of skill.

Games of chance – essentially gambling – are illegal in India except a few states including Goa, Barde said, but games of skill are legal even if played for real money.

Vijaykumar, who was part of a Tamil Nadu four-member committee headed by retired judge K Chandru to study the effects of online gaming, said online games of chance, including rummy and poker, were major causes of suicides in the state.

In 2021, Tamil Nadu ranked second in the country in terms of the number of suicides (18,925) after the western state Maharashtra of (22,207). Nationally, bankruptcy is one of the reasons for suicide besides addiction and unemployment, according to the National Crime Records Bureau.

A June report by US-based Sensor Tower, a leading mobile app ecosystem data provider, said the Indian market had the highest number of monthly downloaded games in the world, followed by the United States and Brazil.

The Indian gaming market, valued at US$1.02 billion in 2020, is expected to reach US$4.88 billion by 2026.

Experts said the cheap 4G internet connection and increasing number of smartphone users were the main reasons behind the industry’s growth, with RummyCircle, Rummy Passion and PokerBaazi as its key players.

The Indian Cellular and Electronics Association – the apex body of the mobile and electronics industry – and consulting firm KPMG had predicted in 2020 smartphone users in India would rise to 820 million by this year. There are about 750 million smartphone users now.

Growing at a compound annual growth rate of 38 per cent, Barde said the 15-year-old online gaming sector in India held significant potential for overall “economic growth and employment opportunities”.

Chandru, however, justified the ban, saying there would be a “sense of fear among people” about taking part in games of chance now that they were illegal in Tamil Nadu.

But Unmesh Joshi, co-founder of Mumbai-based non-profit Responsible Netism, which promotes cyber wellness, said creating awareness about game addiction was essential as a ban alone would not help and many gamers engaged in criminal activities to fund their addiction.

“Many pro gamers also create content on video sharing sites to guide other gamers, and get paid by these sites. Often, they lend money to addicts who play for higher stakes,” Joshi said.

When people start losing money in the game, unsolicited advertisements on gaming sites direct them to loan apps which push them to lose thousands of rupees, according to Chandru.

Tamil Nadu’s new law will penalise people for putting up ads on the banned games.

Creating awareness about game addiction is essential, says Unmesh Joshi, co-founder of Mumbai-based non-profit Responsible Netism. Photo: Shutterstock

But Barde said instead of imposing a ban, the “state must regulate operators” to ensure they do mandatory identity verification to prevent underage gamers from playing real-money games. Operators must also keep gamers’ financial details safe and offer features such as daily spending limits and restricting play for certain periods, he added.

In the past five years, six states including Telangana, Odisha and Nagaland banned online gaming but illegal operators continue to operate.

In 2020, police arrested a Chinese national in Telangana for running online gaming and betting activities worth millions of rupees.

Chandru urged the Indian government to enact a national legislation as only then “an effective ban can be enforced”.

The government, however, was “committed” to start-ups in every aspect of the digital economy including gaming, Rajeev Chandrasekhar, minister of state for electronics and information technology, said in June.

Published in South China Morning Post. October 24, 2022: https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3197090/playing-lives-indian-state-bans-online-gaming-over-addiction-fears-industry-cries-foul

The picturesque Galle Face Green overlooking the Indian Ocean from Sri Lanka’s capital, Colombo, was the epicenter of the “Janatha Aragalaya” — which means “people’s struggle” in the Sinhalese language — that shook the nation earlier this year and forced then-President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to flee. Now, the site is deserted. The tents that housed protesters — teachers, students, lawyers, health workers, farmers, fishermen, trade unionists, transporters and entrepreneurs — since April 9 were demolished last month by security forces soon after former Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe took charge as president of this debt-ridden island nation of 21.6 million people.

But Wickremesinghe is seen by many as an ally of the Rajapaksa family that ruled Sri Lanka for most of the past two decades: Gotabaya’s brother, Mahinda Rajapaksa, who was prime minister under him, served as president from 2005 to 2015. Inflation is at 60%, with severe shortages of fuel, food, medicines and electricity. And protesters are clear: Their struggle isn’t over yet. OZY reports from Sri Lanka on what’s next for the popular uprising, those who participated in it, and the country they hope to change.

– with reporting by Sonia Sarkar from Sri Lanka

If not now, then when?

At Galle Face Green, the embers of the protest that unseated the Rajapaksas are still visible.

Hundreds of pairs of shoes of protesters, who were allegedly assaulted by police, have been piled up together. Boards reading “Let’s build up a country without enforced disappearances” and “We are our own leaders” stand firmly on the green grass. Public walls are filled with slogans such as “Power To The People Beyond Parliament” and “Ranil Go Home.”

“After police picked up protesters randomly, people are cautious before assembling again for the protests,” 28-year-old Colombo-based civil engineer Nuzly Hameem, who participated in the protests, told OZY. “But that doesn’t mean that people are happy with the current regime. This silence is only a lull before the storm.”

In April, on the way to his office a little over a mile from Galle Face Green, Hameem came across hundreds of tuk-tuk drivers sleeping on the pavement while they queued up for days in front of fuel stations. At home, Hameem faced power cuts for 13 hours a day, and the prices for essential food items skyrocketed as well. “It became worse and worse. People realized that if we don’t protest now, then when,” said Hameem.

At Galle Face Green, ordinary citizens shouted “Go Gota Go” for months, leading up to Rajapaksa leaving the country. Wickremesinghe, the former prime minister, was then elected as president not by the people but by parliamentarians, even though he lost the last election and his party has no members of its own in parliament.

Thisara Anuruddha Bandara, 28, who was arrested twice since April on charges of promoting “feelings of disaffection” toward the state and obstructing the entrance of the presidential secretariat, told OZY that the goal is to “unseat” all who protect the “corrupt system.” About one in every four Sri Lankans is between 15 and 29 years old, the demographic that formed the backbone of the anti-government protests.

But do they have a roadmap ahead?

President Wickremesinghe has held talks with a handful of protesters to discuss the future. Vimukthi Dushantha, whose Black Cap Movement withdrew from the protests soon after Wickremesinghe took power, is among those who have participated. Wickremasinghe has used a state of emergency and anti-terrorism laws to crack down on protesters. The Black Cap Movement wants these crackdowns ended in order to “create space for participation of citizens in the legislature in the next six months,” Dushantha said in an interview with OZY. “We want elections soon after these reforms.”

But Bandara doesn’t think Wickremesinghe has any intentions to bring any “reforms,” given his “military approach” towards protesters. Police, who enjoy sweeping powers to make arrests under emergency laws, have randomly picked up protesters and framed them on terrorism charges. Wickremesinghe’s brutal clampdown on dissent has been criticized by the European Union as well.

What protesters want is a Sri Lankan parliament that better reflects the country. The average age of lawmakers is 53, while the median age of the population is almost 20 years younger. Climate change activist Maleesha Gunawardana said to OZY that the nation needs more women in the parliament who will work for the future generation. Currently only 12 out of Sri Lanka’s 225 national lawmakers are women.

The protests were largely driven by ordinary citizens without political affiliation. But the National People’s Power (NPP), a coalition of over 27 opposition parties, worker unions and women’s rights groups led by Janatha Vimukti Peramuna (JVP) and its breakaway faction, Frontline Socialist Party (FSP), organized several rallies since March. Rev. Nandana Manatunga, head of the Catholic nonprofit Human Rights Office, told OZY that, ideally, there should be a “strong coalition of the opposition” but that will be a “bit difficult” because of the government’s repressive measures. “The government may launch a crackdown on the opposition too, just the way it is punishing the activists,” Manatunga said.

Meanwhile, Hameem believes that an “early” election is a must to get rid of government repression. What’s needed, he said, is a more “educated” cohort of parliamentarians — at least 100 new faces — unlike the current set of legislators whose educational qualifications are shrouded in opacity. “Change may not come in the first five years, but it will eventually come in their second or third term,” said Hameem.